Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange grew up in a middle-class family in New Jersey. Her father, Heinrich Nutzhorn, was a lawyer, but also held several respected positions in local businesses, politics and the church. Her mother, Johanna, managed the household. Both parents were proponents of education and culture, and exposed both Dorothea and her brother Martin to literature and the creative arts.

At the age of seven, Dorothea contracted polio, which left her with a weakened right leg and foot. Always conscious of its effects, she once said that, "[polio] was the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me". Her parents divorced five years later; Dorothea never forgave her father, whom she blamed for ending the marriage. She eventually dropped his surname, instead taking her mother's maiden name for her own.

Without Heinrich, the family moved in with Johanna's mother, Sophie, a seamstress with an artistic touch. Although this arrangement was not ideal for Dorothea, who had a mutually antagonistic relationship with her grandmother, Sophie's love of "fine things" and artistic sensibility left its mark on the young girl.

Lange showed little interest in academics, and after high school announced to her family that she intended to pursue photography. Looking for work, she approached Arnold Genthe, one of the most successful portrait photographers in the nation. He hired her as a receptionist, but taught her skills of the trade, including how to make proofs, retouch photographs, and mount pictures. Although she worked for several different photographers after Genthe, she always remembered his sense of aesthetics and the importance he placed on high quality, not unlike the lessons her grandmother taught her.

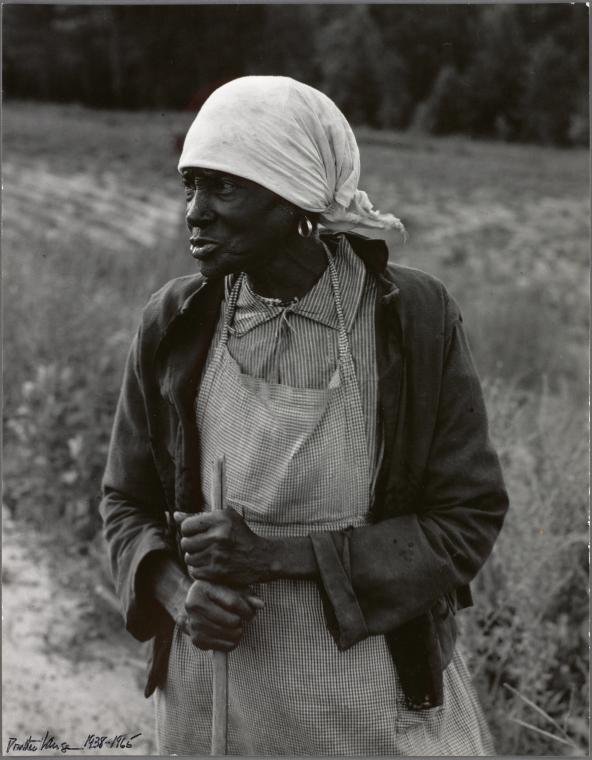

Dorothea Lange, Ex-Slave With Long Memory, Alabama, 1938. © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor.

Lange also took a photography course with Clarence H. White. White was influenced by the Pictorialist style of photography, which cultivated many of the effects of fine painting, but he also encouraged his students to individualize their pictures by developing a unique point of view, and his assignments often involved photographing every day subjects to truly see them. Lange used this concept later in life, where photographs reveal the extraordinary within the average working American.

Lange settled in San Francisco in 1918. Through friends, she made connections with wealthy business owners and gallery patrons and was soon able to open her own successful portrait studio. Lange considered her work a trade rather than an art and primarily sought to satisfy her client's desires. She married Maynard Dixon, a well-known muralist, with whom she had two sons, and her marriage drew her deeper into the California art community, but the Great Depression proved a strain on both her marriage and career. Seeing the effects of financial hardship on the people around her, she grew increasingly dissatisfied with portrait work. She took to the streets of San Francisco - documented and sought new techniques, experimenting with close-up shots and simple compositions that emphasized shape and form, rather than focusing only on the subject.

In 1935, Lange was one of the photographers asked to assist with an economic research study led by Paul Taylor, who later became her second husband. Impressed by her work, Taylor recruited her for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a division of the U. S. government that represented the interests of American farm workers, including tenant farmers and people of color. During this time, Lange recorded the conditions of workers living in poverty-stricken areas of the West coast, the South and the Midwest, including the camps that resulted from the Dust Bowl migration. The photographs from her tenure with the FSA have become iconic within American history and photography.

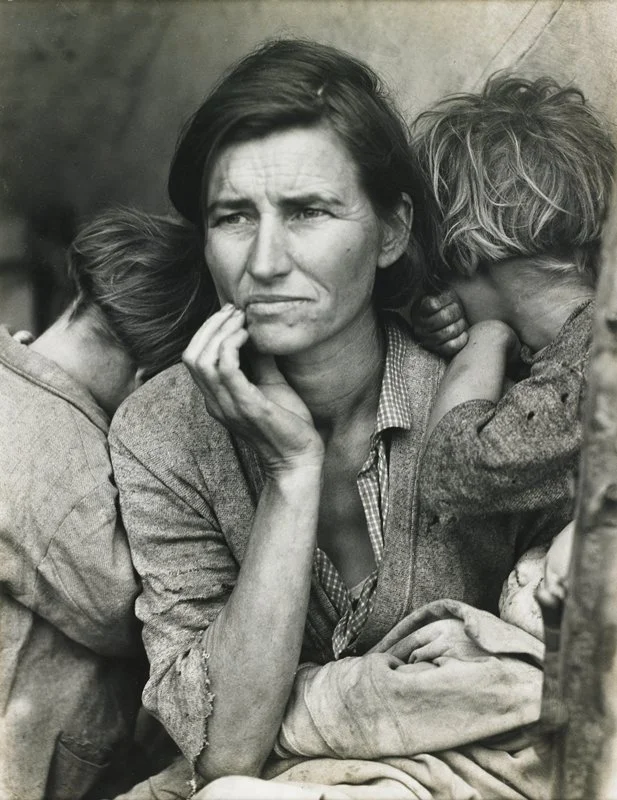

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, Gelatin silver print, 13 5/16 x 10 5/16 in, 1936. The Alfred and Ingrid Lenz Harrison Fund.

Out in the field, Lange developed her signature style of photography. Abandoning wide-angle landscape views, she reverted to practices used in her studio and asked the workers to share their stories. These mature photographs often represent intimate portraits, and the captions relate information gleaned from her conversations.

Within this body of work, four main themes emerged. Primarily, the photographs emphasize the relationship between the land and the people, clearly illustrated by the growing hopelessness of the workers unable to revitalize their sterile environments. A feeling of desertion also runs through her depictions of empty streets, abandoned houses, and fields bare of crops. Among her portraits, Lange often represented the depressed man, left idle and dispirited from lack of work. Conversely, images of the strong female heroic figure are also prevalent in her photographs.

Lange became the first female photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1940. First postponed due to family obligations, she later requested another deferment when she was asked to document the internment of the Japanese population after the Pearl Harbor attack. The commission came from the government, yet the resulting photographs threatened to be so controversial that they were impounded for the duration of the war and Lange was not able to see them until twenty years later. They create a subtle yet startling picture of the racism practiced by the American government against its own citizens, and many of the photographs are taken in her signature portrait style, lending a sense of dignity to the people who had been forced from their homes. Lange was able to capture the strength and resilience of the Japanese community, which continued to organize cultural activities and published their own newspapers within the camps.

Disillusioned with the failure of her work to enact true social or political change, Lange withdrew from photography for several years. Multiple ailments, including lingering effects from her bout with polio, also took their toll on her health. She briefly taught a photography course at the California School of Fine Arts, using methods that echoed White, her old teacher. By 1950, however, she had resumed working and agreed to participate in the Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Dorothea Lange, Members of the Mochida Family Awaiting Evacuation, 1942. National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the War Relocation Authority.

Lange was contracted by Life to photograph the Mormon society in Utah and the Irish community in County Clare, but these articles also failed to communicate her intentions for social change. When Taylor was appointed a foreign diplomat, she gained the opportunity to record life across the continents, many of which proved more destitute than the conditions she experienced during her work with the FSA. These trips ended as her health continued to deteriorate, although she remained energetic enough to collaborate with New York's Museum of Modern Art on her first solo exhibition. Lange passed away from esophageal cancer in October of 1965, less than three months before her retrospective opened.

Dorothea Lange is an inspiring example of the opportunities that lay open to strong, independent women photographers in the modern era. Her greatest achievements lie in the photographs she took during the Depression. They made an enormous impact on how millions of ordinary Americans understood the plight of the poor in their country, and they have inspired generations of campaigning photographers ever since. But her work after the 1930s also deserves note, not least her involvement with establishing the Aperture Foundation and magazine. Several awards have been set up in her name, including the Lange-Taylor prize for excellence in documentary studies and the Lange Fellowship for documentary photography. Her archives have been preserved near her hometown at the Oakland Museum of California.