Harriet Powers

Harriet Powers was born into slavery near Athens, Georgia in 1837. The majority of her early life was spent on the plantation of John and Nancy Lester in Madison County, Georgia. Sewing in Antebellum America was an essential skill most enslaved women learned at an early age from the other slaves, and sometimes from the mistress of the plantation.

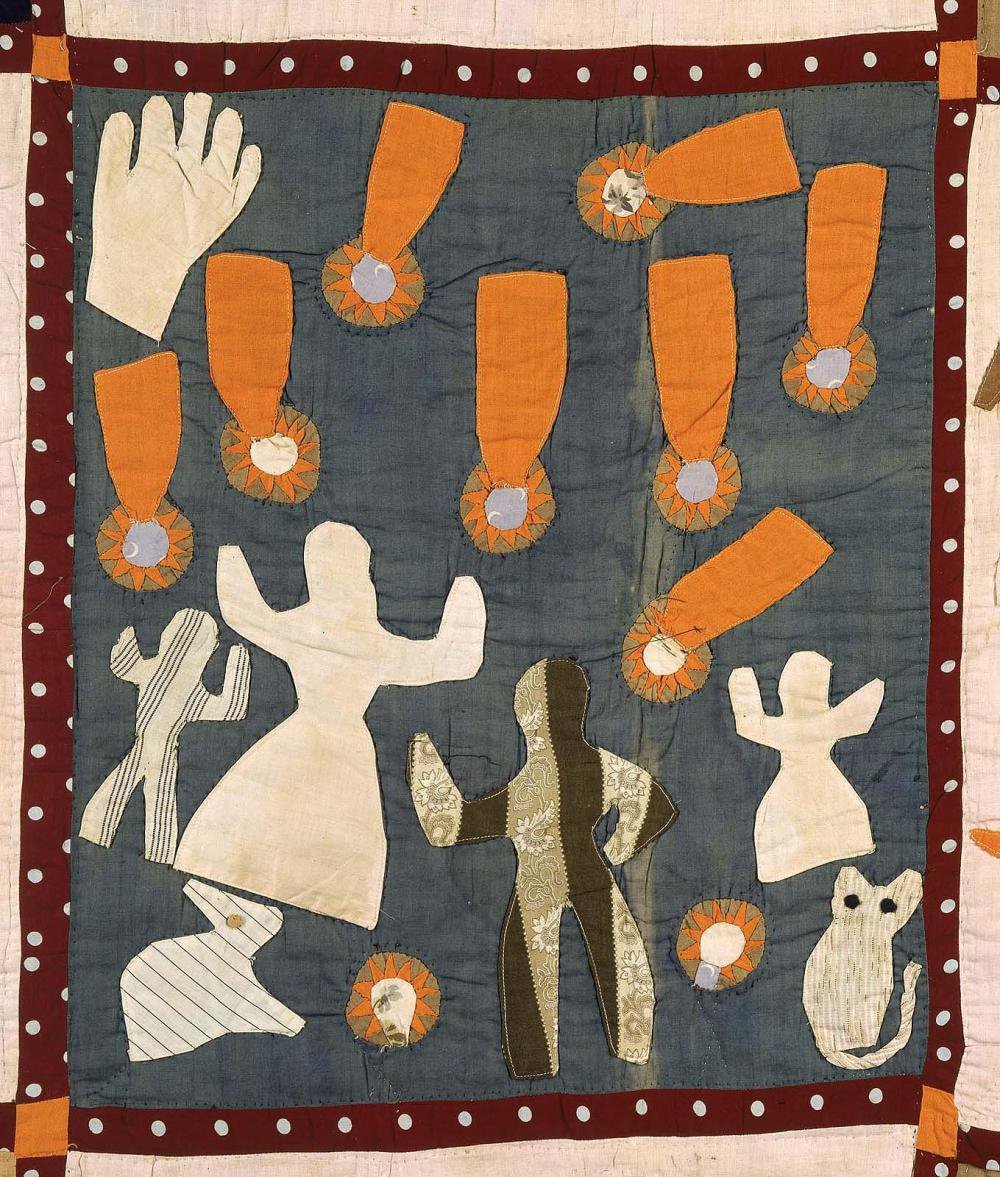

Harriet Powers, Pictorial Quilt, 1895, cotton plain weave, pieced, appliquéd, embroidered, and quilted, 175 x 266.7 cm, Boston Museum of Fine Arts

Powers married at nineteen, had nine children, and lived to become free during an era of extreme challenges and often violent obstacles for African Americans and especially Black women. Very little is known about the specifics of the Powers’ life. However, her masterful technical skills and visionary artistic brilliance created two extraordinary hand-and machine-pieced and stitched storytelling quilts: Bible Quilt (1886) and Pictorial Quilt (1898), now in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. These two quilts remain as critical, unparalleled examples of works executed by a woman of African descent “telling” her stories of her experiences as a Black woman that is crucial to a more authentic narrative of the whole history of America’s past, present, and future through the artistry of textile creations.

Harriet Powers, Bible Quilt, 1885-1886, padding, cotton, 191 x 227 cm, National Museum of American History

Powers could not read or write but through her technical prowess with a needle, thread, appliquéd fabrics and her innate observations of environmental phenomena and impassioned biblical beliefs, she visualized monumental artistic vision and storytelling that combined her witness of natural occurrences that she connected to the powers of an almighty God. These two quilts are the only known survivors of Powers’ creativity. They demonstrate how sewing became an act of “subversive stitching” – a metaphor for resistance, resilience, and a means to express her artistic intent, intellect, and agency. These extraordinary quilts reveal the masterful genius of an enslaved woman having to negotiate the extremes of a harsh and brutal existence. Historians, critics, and curators have classified Powers as a “folk” artist given the too often male-driven biases of America’s attitudes and practices towards poor, undereducated, citizens of color — even though she likely learned her craft from enslaved Africans who came to the Americas with generations of technical knowledge and complex aesthetic traditions embedded in their memories.

Harriet Powers, Pictorial quilt, detail, 1895-1898, cotton plain weave, pieced, appliquéd, embroidered, and quilted, 266.7 x 175 cm, Museum of Fine Arts Boston

African oral transmission of knowledge prevailed, leaving indelible artistic imprints that transcended the fact that reading and writing were forbidden for enslaved peoples. African aesthetic and oral traditions are not “folk” idioms. African cultures have been established through centuries of complex practices and belief systems, grounded in those ancient and ancestral legacies. Powers was an agent of change, hidden in plain view, inscribing with a needle, thread, and scrapes of fiber the tenacity and brilliance of an aesthetic that continues to survive through innovation, improvisation and invention against all odds.